The emergency

Last update: 30-07-2020

The science is clear: It is understood that we are facing an unprecedented global emergency. We are in a life or death situation of our own making. We must act now.

“We are in a planetary emergency.”

“Based on sober scientific analysis, we are deeply within a climate emergency state but people are not aware of it”

“Climate change is a medical emergency … It thus demands an emergency response…”

“This is an emergency and for emergency situations we need emergency action.”

Table of contents

- The emergency

- Warnings

- Nature loss

- Air

- Water

- Earth

- Food

- The urgency

- “Faster than expected”

- Risk and the precautionary principle

- Feedbacks and tipping points

HUMAN ACTIVITY IS CAUSING IRREPARABLE HARM TO THE LIFE ON THIS WORLD

Many current life forms will be extinct by the end of this century. We may right now be causing the Sixth Mass Extinction in Earth’s history.

The air we breathe, the water we drink, the earth we plant in, the food we eat, and the beauty and diversity of nature that nourishes our psychological well-being – our very health – all are being corrupted and compromised by the human values behind our political and economic systems and consumer-focussed lifestyles.

The effects of climate and ecological disruption that we are experiencing now are nothing compared to what could come. Catastrophic effects on human society and the natural world may spiral out of control if this climate and ecological emergency is not addressed in time.

- Biodiversity Loss

- Sea level rise

- Desertification

- Wildfires

- Water shortage

- Crop failure

- Extreme weather

THE COMBINED RESULT OF THESE DESTABILISING EVENTS WILL BE:

- Millions displaced

- Disease

- Increased risk of wars and conflicts

- Impacts on human rights

“The world has never seen a threat to human rights of this scope… The economies of all nations, the institutional, political, social and cultural fabric of every state, and the rights of all your people, and future generations, will be impacted.”

We must act while we still can. We have run out of the luxury of time to react incrementally. But our leaders are failing in their duty to act on our behalf.

We must act while we still can. We have run out of the luxury of time to react incrementally. But our leaders are failing in their duty to act on our behalf.

We must immediately begin improving carbon absorption, drawing it down and locking it up again, while also reducing emissions. We must stop the harm we are causing the natural world that is pushing other species to the point of extinction. If we don’t address the causes of climate change in time, communities across the world stand to simultaneously face multiple intensifying climate hazards that pose a broad threat to humanity.

The task before us is daunting but big changes have happened before.

Let’s make a better world.

WARNINGS

WE’VE BEEN WARNED AGAIN AND AGAIN…AND AGAIN

1992

In 1992, the Union of Concerned Scientists including the majority of living science Nobel laureates, penned the “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity”calling on humankind to curtail environmental destruction and warning that “a great change in our stewardship of the Earth and the life on it is required, if vast human misery is to be avoided.”

The authors of the 1992 declaration feared that humanity was pushing Earth’s ecosystems beyond their capacities to support the web of life. They described how we are fast approaching many of the limits of what the biosphere can tolerate without substantial and irreversible harm. They implored that we cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and phase out fossil fuels, reduce deforestation, and reverse the trend of collapsing biodiversity.

2017

In 2017, humanity was given a second notice. Over 15,000 scientists signed a new and even more urgently worded letter which warned that “To prevent widespread misery and catastrophic biodiversity loss, humanity must practice a more environmentally sustainable alternative to business as usual. This prescription was well articulated by the world’s leading scientists 25 years ago, but in most respects, we have not heeded their warning. Soon it will be too late to shift course away from our failing trajectory, and time is running out. We must recognize, in our day-to-day lives and in our governing institutions, that Earth with all its life is our only home.”

2019

In 2019, 11,000+ scientists strengthened the alert with a ‘World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency’ stating, “Scientists have a moral obligation to clearly warn humanity of any great existential threat … Based on this obligation and the data presented below, we herein proclaim … a clear and unequivocal declaration that a climate emergency exists on planet Earth.”

FINAL NOTICE

This is our final notice. We must act now.

“We face a direct existential threat…Our fate is in our hands.”

If we do not change course by 2020, we risk missing the point where we can avoid uncontrollable climate and ecological breakdown, with disastrous consequences for people and for all life on Earth.

NATURE LOSS

The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report produced in 2019 shows the biodiversity crisis is on a par with the threat posed by climate change. The main direct causes of biodiversity loss are habitat change, direct exploitation (e.g., fishing, hunting and logging), invasive alien species, pollution (including nutrient loading), and climate change.

A “biological annihilation” of wildlife in recent decades means that we may be heading for the Sixth Mass Extinction in Earth’s history. Globally species are going extinct at rates up to 1,000 times the background rates typical of Earth’s past. Animal populations are dwindling and disappearing on land and in the oceans.

Once upon a time, biodiversity in the Netherlands was abundant. By 1900, biodiversity was down to 40%, and by 2010, only 15% of original biodiversity was left. In concrete terms, a whopping 614 animal species have disappeared since 1900. In order to counter this, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was drafted in the context of the UN, to which the Netherlands is a party. In 2010, concrete targets were formulated, but research by Wageningen University & Research (WUR) indicates that the Netherlands will miss some of these targets. In open areas such as heathlands and on farmland, the number of wild animals has on average decreased by half between 1990 and 2020, which may be attributed to a high level of nitrogen deposition (commonly referred to as “nitrates from agriculture”). In Europe, the Netherlands are also the biggest emitter of nitrogen per acre, with emissions that are four times higher than the European average. In 72% of Dutch nature areas, too much nitrogen is deposited. In addition, butterfly populations are dwindling, and the number of farmland birds has dropped by 30% since 1990. Of all species in the Netherlands, almost 40% are on the IUCN Red List, including the fire salamander, the black-tailed godwit, and the pine marten. In the Netherlands, protection also includes habitat types, such as riffs, dune forests, and wet meadows. In total, there are 52 of these protected habitat types, and the status of only six is “favourable”; the status of the remaining 46 areas is either “inadequate” or “unfavourable”. Fish stocks in the Netherlands are also far from sustainable. According to the Dutch Marine Strategy, only 26% of commercial fish and shellfish stocks enjoy a healthy environmental status.

Looking at the UK for example, the 2016 State of Nature report found that the UK was “amongst the most nature-depleted countries in the world”. One in five British mammals are at risk of being lost from the countryside with the populations of hedgehogs and water voles declining by almost 70% in just the past 20 years. And the most recent report by the British Trust for Ornithology found that more than a quarter of British bird species are threatened, including the Puffin, the Nightingale, and Curlew. Across Europe the average population size of farmland bird species has fallen by 55% in just the past three decades.

Globally, the latest Living Planet Index estimates an average decline of 60% in the population size of thousands of vertebrate species around the world between 1970 and 2014 – with even faster declines in freshwater populations.

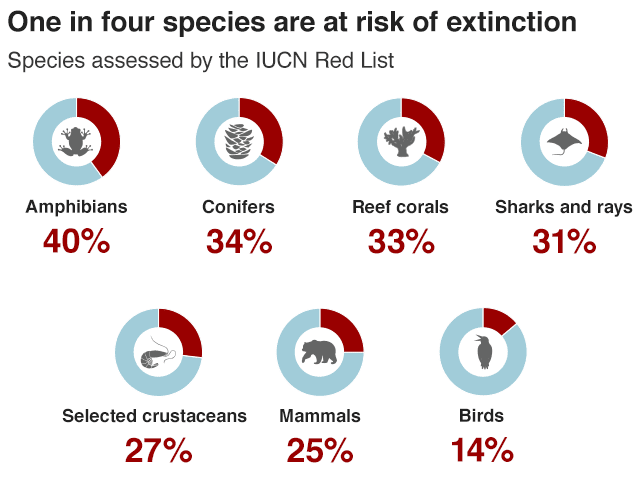

More than a quarter of approximately 100,000 species assessed by the IUCN are threatened with extinction; 40% of all amphibians, 25% of all mammals, 34% of all conifers, 14% of all birds, 33% of reef-building corals, 31% of sharks and rays. IPBES estimated that a million species of animal and plant are already threatened with extinction because of human action.

Coral reefs are suffering mass die-offs from heat stress. These events are becoming much more common with back to back die-offs on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia in 2016 and 2017. The predictions are that at just 2°C of warming above pre-industrial temperatures these heat waves will occur on an annual basis and coral reefs would become functionally extinct. According to the 2018 IPCC special report, 70-90% of all coral reefs are expected to die with just 1.5°C of warming above pre industrial levels, and more than 99% at 2°C – the “safe” level of warming in international negotiations. That is near total destruction of some of the most important and diverse ecosystems on the planet, which provide food and protection from storms for hundreds of thousands of people.

“20 years from now, every summer will be too hot for corals: they will disappear as dominant members of tropical reef systems by 2040-2050. It’s hard to argue it any other way.”

INSECT DIE-OFF

There is strong evidence that many insects are in trouble, from a wide range of pressures including habitat loss, agro-chemical pollutants, invasive species and climate change.

In Great Britain, three times as many pollinator species are declining as are increasing, and neonicotinoid pesticides are driving some bee populations extinct.

A 27-year long population monitoring study in a set of nature reserves across Germany revealed a dramatic 76% decline in flying insect biomass.

And a new study by Dutch scientists found that Butterfly numbers had fallen by an average of over 80% in the last 130 years. With the authors concluding that “industrial agriculture is simply leaving hardly any room for nature.”

Insect and invertebrate declines are not just limited to Europe, this is a worldwide issue. A review of the most comprehensive studies conducted used a global index for invertebrate abundance and estimated a 45% decline over the last four decades.

Many birds feed on insects, so insect declines have already led to drastically fewer birds in gardens and in the countryside. But it isn’t only the birds that depend on insects. Insects pollinate many of our crops, help fertilise the soil they grow in, and help control outbreaks of crop pests and of organisms that cause disease in people and livestock. If insects are in trouble, so are we.

“It should be of huge concern to all of us, for insects are at the heart of every food web, they pollinate the large majority of plant species, keep the soil healthy, recycle nutrients, control pests, and much more. Love them or loathe them, we humans cannot survive without insects.”

AIR

GLOBAL HEATING: GREENHOUSE GASES

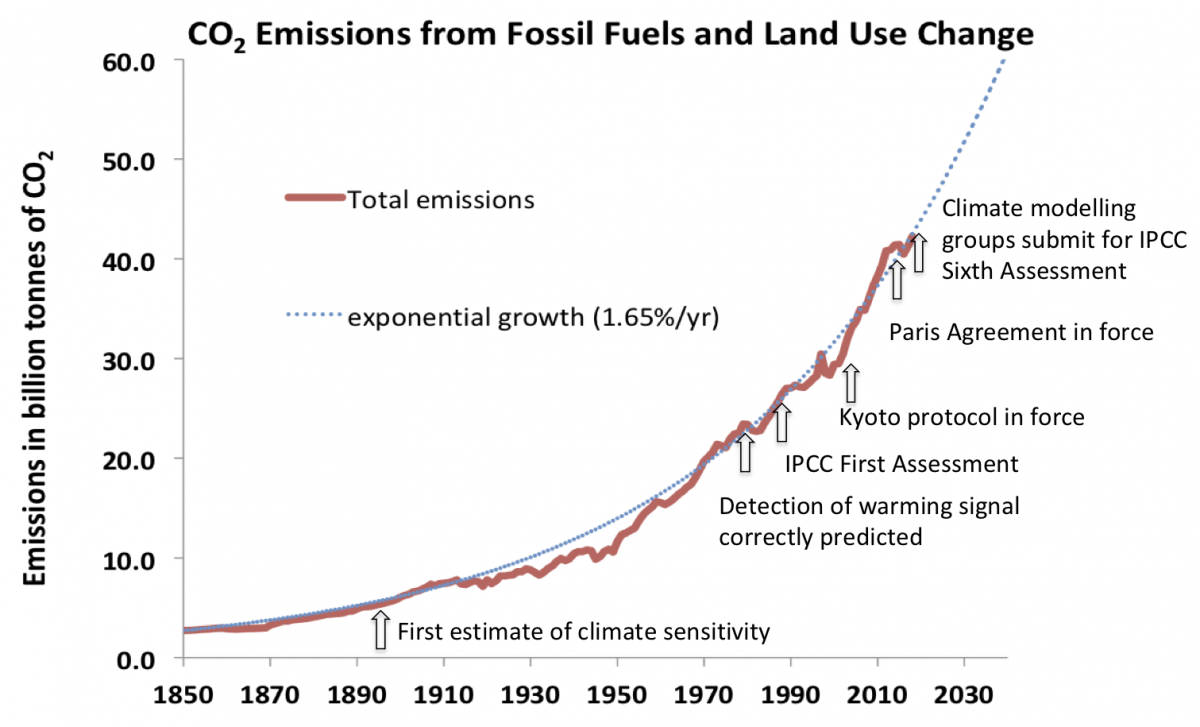

Our emissions are still increasing!

Global rise of CO2 emissions per year from fossil fuels and land-use change, which have shown no sign of slowing down despite over thirty years of climate negotiations.

Carbon dioxide concentrations are at a record high of 411 parts per million (ppm) (an increase of over 45% on pre-industrial levels). Concentrations are now at the highest levels in at least the last 3 million years (i.e. since before modern humans had even evolved on this planet).

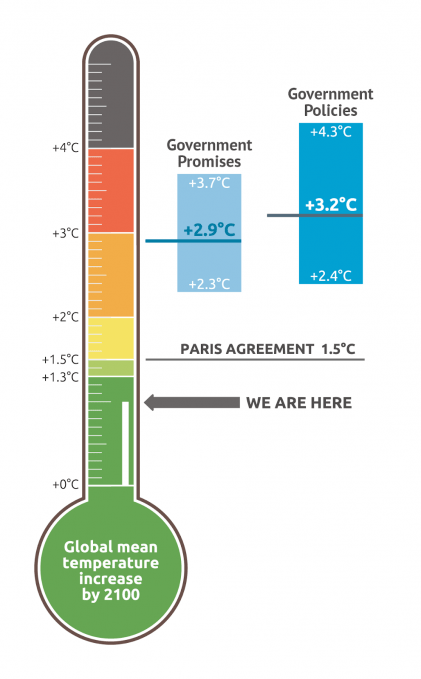

To stabilise temperatures emissions need to reach net-zero. Indeed the climate will keep slowly warming for around 10 years after CO2 emissions stop due to thermal inertia! The longer we delay the harder it becomes to stabilise temperatures at a safe level. Unfortunately, because of years of delay and inaction we have reached a crisis where we will only meet our targets if we to take urgent emergency action!

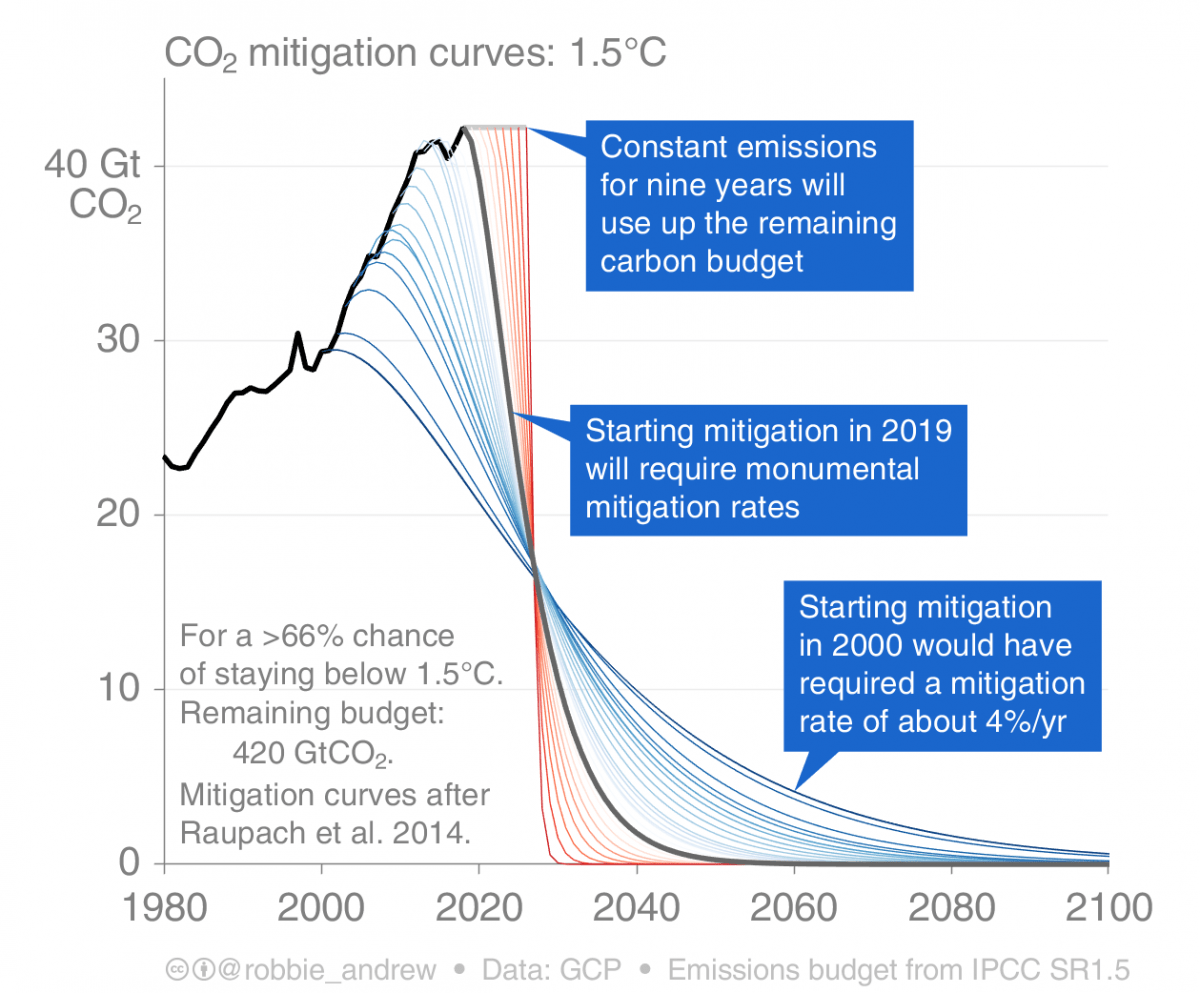

This graph shows the budget for a 2/3rds chance of staying below the agreed target of 1.5͒ C of global heating, you can see that any delay in reducing emissions requires even steeper cuts to occur in the future. Because of past delay there is now no alternative but to really rapidly cut emissions if we are to still stay within this target.

Carbon dioxide is not the only greenhouse gas scientists are concerned about, methane, nitrous oxide, ozone and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) all cause significant additional heating. Methane, in particular, is the second largest contributor to global heating after CO2. Each tonne emitted can cause approximately 28 times as much warming as CO2 over a 20 year period, but a massive 84 times as much over 100 years! The oil and gas industry, waste sector and agriculture contribute heavily to the amount of methane in our atmosphere.

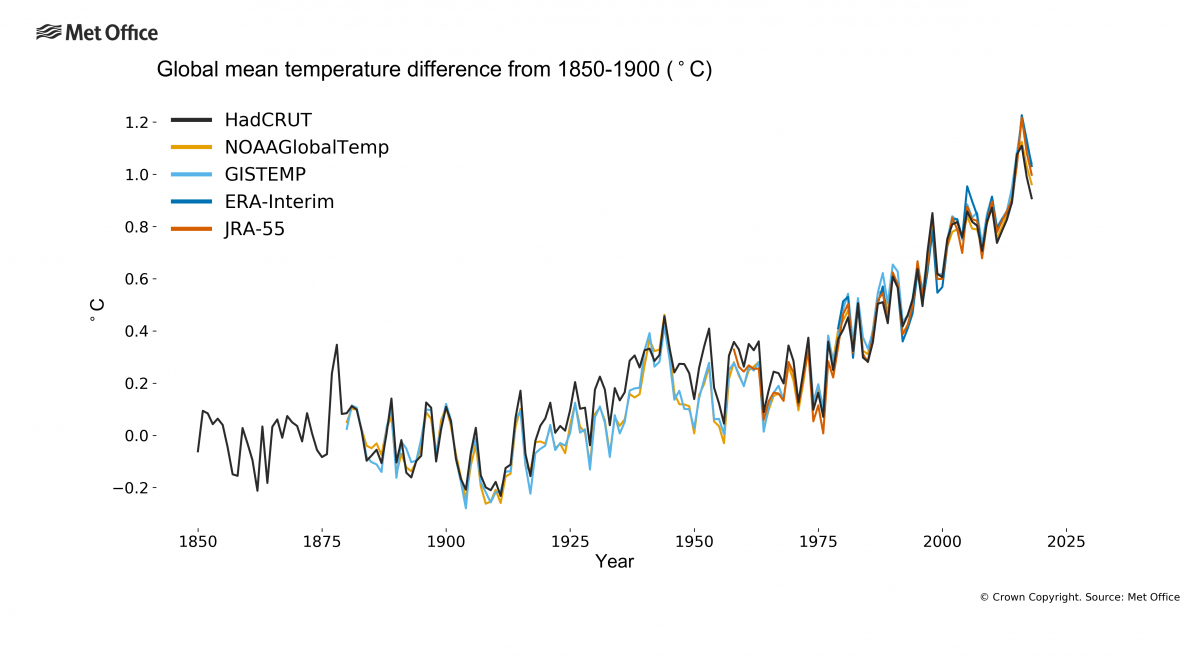

Overall, human activities have caused the planet’s average surface temperature to rise about 1.1°C since the late 19th century. Most of the warming occurred in the past 35 years.

Globally, the past four years (2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018) have been the hottest on record, and the 20 warmest have all occurred in the past 22 years.

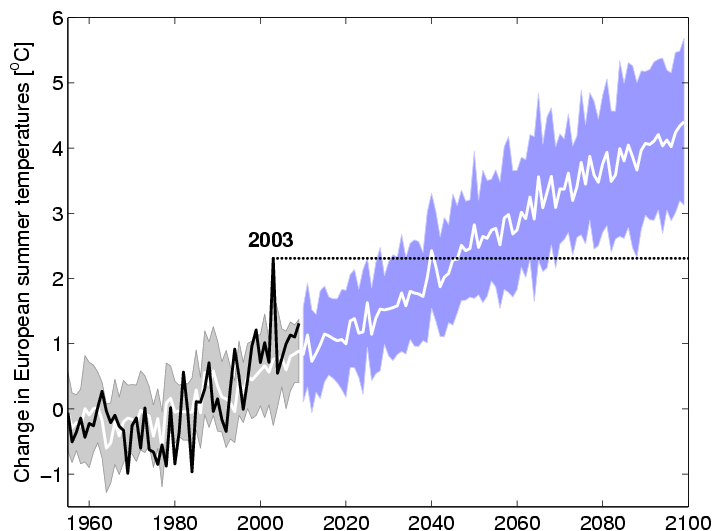

As global temperatures rise we see an increase in extreme weather events such as heatwaves. For example, scientists from the UK Met Office who examined the extreme heat wave which struck Europe in the summer of 2003 (which is now thought to have killed 70,000 people) concluded that “it is very likely…that human influence has at least doubled the risk of a heatwave exceeding this threshold magnitude.” More recently, it has been estimated that the record breaking European summer of 2019, which killed almost 1500 people in France, has been made at least five times more likely due to human induced climate change. If we carry on burning fossil fuels, such extreme heatwaves will become an average summer for Europe by 2040 and almost all summers will be hotter than that by 2060! As shown in this graph:

Across the globe, calculations show that record breaking extreme temperatures become far more probable due to human-induced warming (for example 2010 Syria; 2013 Korea; 2014 California; 2018 UK). These changes represent a big step into the unknown. By 2050, under even a relatively optimistic emissions scenario, it is predicted that 22% of major cities will be heated to the point that their climate is unlike any currently existing city.

A 2018 study shows how deadly heat waves may limit habitability of one of the world’s most populous regions in the world. Concluding that continued burning of fossil fuels would lead to heat extremes that exceed “the threshold defining what Chinese farmers may tolerate while working outdoors.”

Overall, climate change is already having severe impacts and making extreme weather more likely across the world.

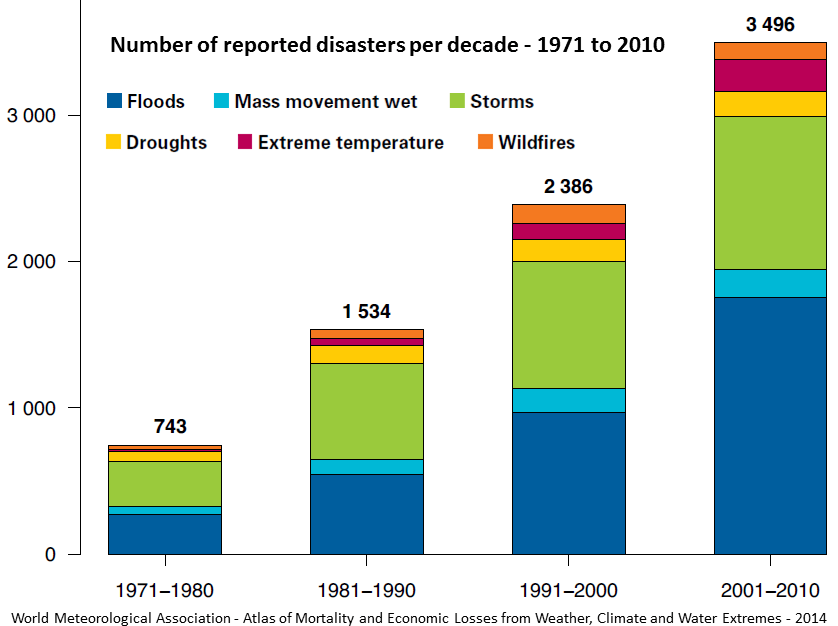

World Meteorological Organization data shows that there has been a dramatic increase in the number of extreme weather disasters around the globe.

AIR POLLUTION

All forms of pollution were responsible in 2015 for an estimated 9 million premature deaths—16% of all deaths worldwide. Pollution is thus the world’s largest environmental cause of disease and premature death.

By far the largest proportion of these are from air pollution. Globally, 9 out of 10 people breathe polluted air, ambient air pollution is responsible for 4.2 million deaths and household air pollution an additional 2.8 million deaths. Most of these deaths occur in low-middle income countries and are largely preventable by using modern technologies, such as cleaner fuels or electricity to replace inefficient solid-fuel burning cookstoves, or solar powered lights instead of kerosene lamps.

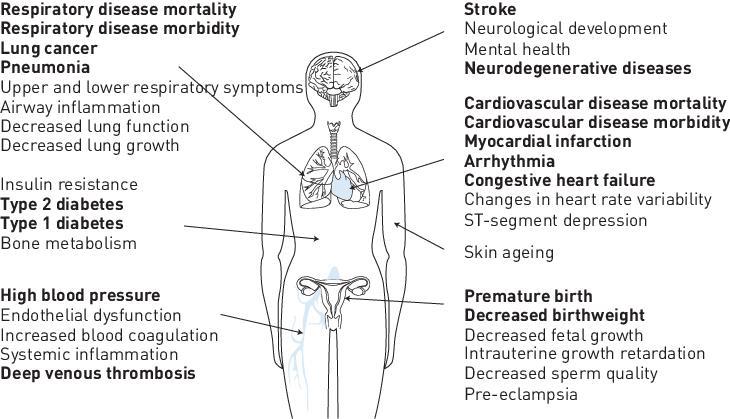

The vast majority of these deaths are due to exposure to air pollution, mostly from small particles that can penetrate deep into the lungs. Young children, those with preexisting health conditions such as asthma and old people are particularly vulnerable. Exposure to air pollutants has been linked to a huge range of diseases, from lung cancer and respiratory infections to stroke, dementia and even diabetes!

Het overgrote deel van deze sterfgevallen overlijdt door blootstelling aan luchtvervuiling, vooral in de vorm van fijnstof, dat diep in de longen kan doordringen. Het zijn vooral jonge kinderen, ouderen en mensen met astma en andere gezondheidsproblemen die er kwetsbaar voor zijn. Een groot aantal verschillende ziekten en aandoeningen, van longkanker en ademhalingsziekten tot beroerten, dementie en zelfs diabetes zijn met blootstelling aan luchtverontreiniging in verband gebracht.

Summary of health outcomes and biomarkers known to be affected by exposure to air pollution, from Thurston et al., 2017.

WATER

DROUGHT AND SCARCITY

Water withdrawals grew at almost twice the rate of population increase in the twentieth century.

The global water cycle is intensifying due to climate change. A 2018 UN report highlights that at present, an estimated 3.6 billion people (nearly half the global population) live in areas that are potentially water-scarce at least one month per year.

Rising temperatures will melt at least one-third of the Himalayan glaciers by the end of the century even if we limit the global temperature rise to 1.5°C. Melting glaciers in both the Andes and the Himalayas threatens the water supplies of hundreds of millions of people living downstream.

A severe drought in Cape Town in 2018 led to severe water restrictions being put in place. The city came to within days of turning off its water supply – dubbed ‘Day Zero’. Climate scientists have now calculated that climate change has already made a drought this severe go from a one in 300 year event to being a one in a hundred year event. At 2°C of warming a drought of this severity will happen roughly once every 33 years.

RISING SEAS

Sea level is rising faster in recent decades. Sea level rise is caused primarily by two factors related to global warming: the added water from melting ice sheets and glaciers; and the expansion of seawater as it warms. Sea level rise will cause inundation of low lying land, islands and coastal cities globally.

As sea levels rise higher over the next 15 to 30 years, tidal flooding is expected to occur much more often, causing severe disruption to coastal communities, and even rendering some areas unusable within the time frame of a typical home mortgage. 2°C warming would threaten to inundate areas now occupied by 130 million people, while an increase of 4°C could lock in enough sea level rise over the coming centuries to submerge land currently home to 470 to 760 million people globally.

The land ice sheets in both Antarctica and Greenland have been losing mass. Both ice sheets have seen an increase in the rate of ice mass loss since 2009. Antarctica is losing six times more ice mass annually now than 30 years ago. The World Meteorological Organisation recently reported that between 2016-2019, sea levels rose by 5mm per year, massively accelerated over the average 3.2mm per year since 1993.

In 2014 a team from NASA found that parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet seem to have begun what they described as an “unstoppable” collapse. If they are correct, this would lock in around a metre of sea level rise. If we continue warming, we risk triggering the collapse of more sectors of the ice-sheets.

“Sea level is rising much faster and Arctic sea ice cover shrinking more rapidly than we previously expected. Unfortunately, the data now show us that we have underestimated the climate crisis in the past.”

OCEAN ACIDIFICATION

The oceans are already 30% more acidic: as carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels dissolves, it alters the chemistry of the sea water. On our current emissions trajectory, in 2100, the pH of the ocean will see a 150% increase in acidity! This will affect marine life from shellfish to whole coral reef communities by removing needed minerals that they use to grow their shells. The oceanic conditions will be unlike anything marine ecosystems have experienced for the last 14 million years.

Present ocean acidification is occurring approximately ten times faster than anything experienced during the last 300 million years, jeopardising the ability of ocean systems to adapt.

Source: Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre

SEA ICE

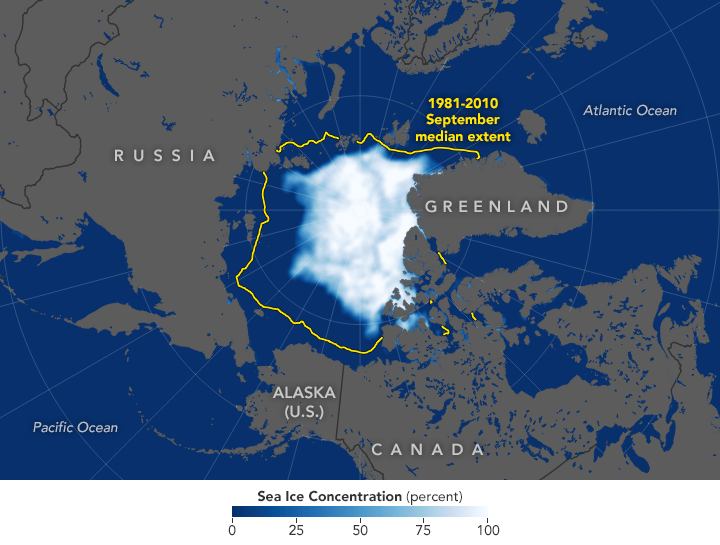

Arctic sea ice is now declining at a rate of 12.8 percent per decade.

Summer Arctic sea ice is predicted to disappear almost completely by the middle of this century if emissions continue at higher rates.

“The Arctic biophysical system is now clearly trending away from its 20th Century state and into an unprecedented state, with implications not only within but beyond the Arctic.”

Scientists are now investigating connections between the huge changes we have seen in the Arctic and changes to the jet stream resulting in increasingly dramatic impacts on extreme weather events at lower latitudes.

Minimum sea ice extent at the end of the melt season on 18 September 2019, the second lowest ever measured, compared to median extent between 1981-2010.

Source: NASA Earth Observatory.

WATER POLLUTION

Nitrates from agriculture are now the most common chemical contaminants in the world’s groundwater aquifers. These pollutants can also dramatically affect aquatic ecosystems, for example, through eutrophication promoted by the accumulation of nutrients in lakes and coastal waters which severely impacts biodiversity and fisheries. Ocean dead zones, areas with zero oxygen, have quadrupled in size since 1950, suffocating the organisms that live in those areas.

Since the 1960s, the number of ocean sites that are suffering from a low oxygen content has increased 15-fold, which may be attributed to the influx of fertilisers as well as ocean heating – warm water can hold less oxygen than cold water.

In the Netherlands, nitrates from agriculture pose serious issues as well. The Netherlands are the biggest emitter of nitrogen per acre in Europe, with emissions that are four times higher than the European average. This makes the Netherlands a world champion and has major consequences for our drinking water. There are over 200 groundwater sites in the Netherlands where drinking water is extracted from the soil. Between 2000 and 2015, fertiliser levels were found to have exceeded legal limits at 89 of these sites. During this period, 21 groundwater plants even had to be closed, as the water had been contaminated to such an extent that it proved too expensive to purify. In addition to nitrate levels, levels of sulphate and nickel were excessive as well, as was the “hardness” (= high mineral content) of the water.

Research from September 2019 indicates that the contamination of groundwater in water extraction areas is increasing and that this is happening at ever greater depths. In addition, our surface water – responsible for some 40% of our drinking water – is also increasingly being contaminated as a result of, among other things, pesticides, salinisation, drug residues, and emerging substances. According to the report, it is also becoming increasingly clear that microplastics, nanomaterials and antibiotics resistance (in animals) may pose a threat.

,,This study paints a worrisome picture. For the 221 drinking water sources in the Netherlands, it is two minutes to midnight.“

“Our children will pay the price for what we are allowing to happen.”

EARTH

WE’RE LOSING OUR SOIL

More than 95% of what we eat draws its existence from soil. It takes about 500 years to form 2.5 cm of topsoil under normal agricultural conditions. Soil erosion and degradation has increased dramatically due to the human activities of deforestation for agriculture, overgrazing and use of agrochemicals.

50% of the planet’s topsoil has been lost in the last 150 years, leading to increased pollution, flooding and desertification. Desertification itself currently affects more than 2.7 billion people. Soil is also being lost to human sprawl. Europe saw an 8.8% increase in artificial land surface between 1990 and 2006.

By 2050, land degradation and climate change together are predicted to reduce crop yields by an average of 10 per cent globally and up to 50 per cent in certain regions. Earthworms cannot compensate for the loss of topsoil as they too have been depleted by 80% or more from intensive agrichemical fields.

Current agricultural practices have led our soils to become more acidic, by an average of ph 0.26 in 20 years, globally. Meanwhile groundwater irrigation is leading to increased salinity with recent projections warning that 50% of all arable land will become impacted by salinity by 2050.

FOOD

One of the world’s leading medical journals, The Lancet, carried out a major review which concluded that climate change poses “the biggest global health threat of the 21st century” because of both the direct impacts of extreme weather events and the indirect disruption to the social and ecological systems that sustain us.

FOOD INSECURITY

More frequent and severe water extremes, including droughts and floods, impact agricultural production, while rising temperatures translate into increased water demand in agriculture sectors.

“We have already observed impacts of climate change on agriculture. We have assessed the amount of climate change we can adapt to. There’s a lot we can’t adapt to even at 2ºC. At 4ºC the impacts are very high and we cannot adapt to them.”

Risk of extreme weather hitting several major food producing regions of the world at the same time could triple by 2040 (1 in 100 year event to 1 in 30).

A recent study looking at the impact of climate change on food production for the top four maize-exporting countries, which currently account for over 85% of global maize exports, found that “the probability that they have simultaneous production losses greater than 10% in any given year is presently virtually zero, but it increases to 7% under 2°C warming and 86% under 4°C warming “

THE URGENCY

What we don’t know is scarier than what we do.

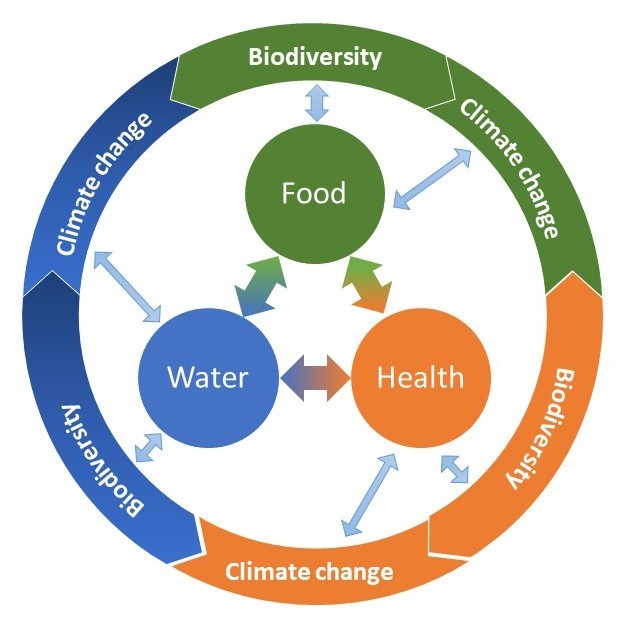

Any of the issues outlined in the content above would be major problems for humanity by themselves. However, in reality the Earth is a huge interlinked system with different parts that all interact with and affect one another. Therefore, to try to understand the full implications of climate change and biodiversity loss, we need to think holistically.

Moreover, it is unrealistic and hubristic to suppose that such holistic thinking could ever be complete or enough. We must accept living in a world that we will never fully understand. The unbelievable complexity of Earth is something before which we should be humble.

While climate deniers and delayers accuse the IPCC of exaggerating the science to suit a political agenda, the truth is if anything the opposite. The IPCC process builds in a requirement toward consensus stronger than that present in ordinary peer-reviewed publications and its summaries for policy makers are edited by politicians and civil servants to make them more politically acceptable.

Under such circumstances, the IPCC is likely if anything to be systematically understating the risks to which we are exposed. There are many times when the published science has underestimated the severity of threats and the rapidity with which they might unfold. This is a phenomenon that historians and scholars of science refer to as ‘scientific reticence’.

“FASTER THAN EXPECTED”

“Climate change is accelerating more rapidly and dangerously than most of us in the scientific community had expected or that the IPCC in its 2007 Report presented.”

“Everything that is expected to result from global climate change driven by greenhouse gases is not only happening, but it’s happening faster than anybody expected.”

“We are seeing increases in extreme weather events that go well beyond what has been predicted or projected in the past. We’re learning that there are factors we were not previously aware of that may be magnifying the impacts of human-caused climate change… Increasingly, the science suggests that many of the impacts are occurring earlier and with greater amplitude than was predicted.”

“…global warming is accelerating. Three trends — rising emissions, declining air pollution and natural climate cycles — will combine over the next 20 years to make climate change faster and more furious than anticipated. In our view, there’s a good chance that we could breach the 1.5 °C level by 2030, not by 2040 as projected in the [IPCC 1.5°C] special report.”

RISK AND THE PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLE

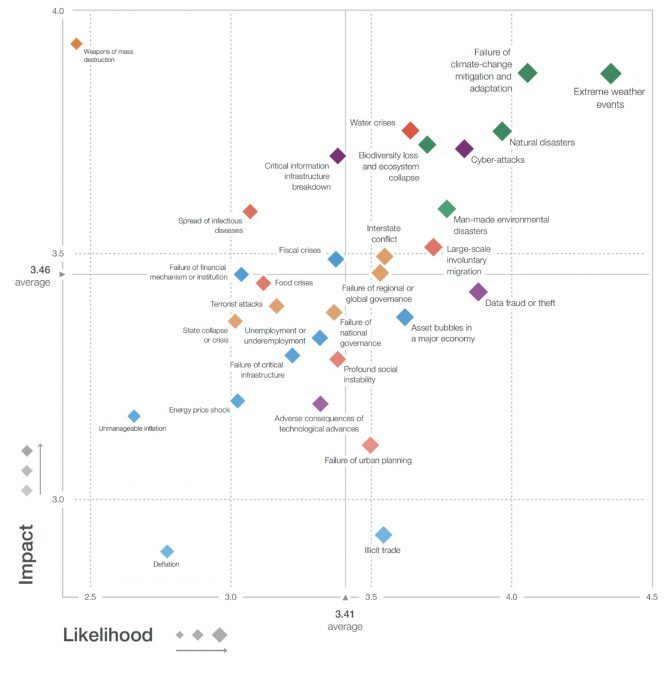

The modelling of climate scientists, which has been amassed and assessed by the IPCC, can only ever provide a probability of certain occurrences – the future can be intelligently guessed at but never fully known. This probability is called “risk”.

In public life we try to prevent even small risks. Because of the small risk of a terrorist carrying a bomb, every airline passenger is screened. Every nut and bolt is regularly checked for integrity. In the UK, the NHS monitors every person over the course of their lives to make sure they are receiving their vaccines and blood pressure checks etc. When paying for drugs they are prepared to spend tens of thousands of pounds to buy someone a single extra year of quality life.

Why, then, are we so slow to prevent the millions of deaths from climate change? The answer may be that we as humans are poor at directly assessing risk. For example, psychologists find that we are excessively swayed by risks we can visualise and not swayed enough by those that we can’t. We can visualise death by an attacker and may be nervous about walking down a dark street: and yet, we find it hard to visualise our death from heart disease and so often fail to maintain healthy lifestyles. in the same vein, we find it hard to be frightened of CO2, despite the fact that it is, ultimately, a deadly gas. This may be one reason humans have been so slow to react to what scientists have told us about the changing climate – we didn’t evolve to be afraid of CO2, or of climate.

We need to stop relying on instinct and to listen to scientists and the numbers they are giving us. The vast unknowable risks to which we are potentially dangerously exposed as a result of anthropogenic climate breakdown and ecosystems breakdown are thus a prime case for the invocation of the Precautionary Principle: that, where there are serious and irreversible risks, it is unwise to wait until all the evidence is in before acting strongly to head off those risks: because by then it will likely be too late. To date, we have not acted cautiously at all.

This is one area where to some extent the Precautionary Principle actually has been used, by the EU to help protect bees. What is needed is for a far more far-reaching application of the PP, in this domain and beyond, if we are to stop being reckless with the future of life.

The vast unknowable risks to which we are potentially dangerously exposed as a result of anthropogenic climate breakdown and ecosystems breakdown are thus a prime case for the invocation of the Precautionary Principle: that, where there are serious and irreversible risks, it is unwise to wait until all the evidence is in before acting strongly to head off those risks: because by then it will likely be too late. To date, we have not acted cautiously at all.

NOW, the precautionary principle warns of the possibility of billions dying as a result of the failure, to date, to stop reckless inertia on climate and on habitat-destruction. It is no answer to such warnings to say “But where is your proof of that scenario?” If we wait for the proof, it will likely be too late.

We have already explained the profound relevance of the PP to our predicament. But there is a conclusion to be drawn which is crucial for understanding our 2nd Demand. Even if there were not already good scientific reason to aim for this country to cease carbon emissions and halt biodiversity loss by 2025, the PP would still enjoin us to do so, so as to minimise potential exposure to the existential risk that climate-deadly emissions and wanton habitat destruction are creating.

FEEDBACKS AND TIPPING POINTS

Some feedback mechanisms exhibit “tipping points” – if temperatures rise above a certain amount they become self reinforcing and will become near impossible to reverse even if emissions then go down. It is very difficult to predict exactly when a tipping point might be breached, however some may kick in with as little as 2°C of warming.

Here, we will highlight a few key feedbacks that are causing climate scientists to be very worried:

KEY FEEDBACKS AND TIPPING POINTS:

MELTING PERMAFROST

The warming in the arctic is causing soils that have been permanently frozen for thousands of years to melt at faster and faster rates. These “permafrosts” contain huge stores of carbon. As they melt, bacteria release this carbon back into the atmosphere as methane or CO2. Because methane can cause much greater warming than CO2 over short periods of time, if the permafrosts melt rate keeps accelerating the methane released would have terrible impacts on climate.

Even at slower rates of melting, the long-term impact of CO2 released from melting permafrosts is a serious cause for concern.

REDUCED CARBON UPTAKE

It appears that since the start of industrialization, increasing photosynthesis by terrestrial vegetation has caused the uptake of about one third of all human CO2 emissions. This effect has so far prevented much worse effects of climate change, since without it we would now have about 450 instead of 411 parts per million CO2 in the atmosphere. Model predictions indicate that at some point climate change will start to make further increases in photosynthesis impossible due to increasing heat stress. The effect can be easily observed in a vegetable garden during the hot period of summer, when plant growth temporarily stops. At a global scale, this can lead to a sudden acceleration of CO2 increase even if human emissions don’t change. In addition, warming also leads to more carbon released from soils, and warming combined with increases in dry and wet extremes leads to more wildfires and reduces standing biomass, also causing more CO2 to be released into the atmosphere. In all cases, extra CO2 in the atmosphere will lead to more warming, which in turn leads to more CO2 release, in a vicious circle called the climate-carbon cycle feedback.

Tipping points in the Earth System at risk of being triggered at different levels of warming and how they may feed back with each other.

Source: Steffen et al., PNAS, 2018.

While feedbacks in the real climate are unlikely to cause “runaway” heating, the longer we emit greenhouse gases and the hotter it gets, the more likely that multiple interacting tipping points could push the Earth into hotter states, from which it will be impossible to return for thousands of years. In short, even if we manage to greatly reduce greenhouse gas emissions to meet the Paris agreement target of keeping below 2°C of heating (taking into account that we are currently on track to 3 or more degrees of heating) there is a small but significant risk that we might trigger irreversible feedbacks that make us overshoot the target. Either if we don’t take radical action, or trigger these tipping points, the outcome would be devastating for natural ecosystems and human societies across the world. We therefore need to make extra effort to urgently reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and aim to keep global temperatures below 1.5°C of warming.